[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;”]S[/dropcap]ince the late 60’s Michael Finnissy has been composing classical work that challenges, shakes and agitates the listener from complacency.

The scope of Finnissy ‘s work is remarkable in its rejection of laissez faire assumptions of what classical music should be and which master it should serve. Continually evolving, for Finnissy fans every decade seems to have a defining event where he’ll receive a lot of press, general acclaim, a consensus that ‘more must be known’, and then a period of silence. But then in age of instant and easy access to art as commodity this relative inaccessibility perhaps serves us well.

As of January 2013, the online compendium of all scholarly journals, JSTOR, cites some 636 articles related to Michael Finnissy, one enthusiastic entry begins:

As of January 2013, the online compendium of all scholarly journals, JSTOR, cites some 636 articles related to Michael Finnissy, one enthusiastic entry begins:

“A Michael Finnissy work is a like a journey from one point to another, along which there are any number of digressions off the ‘main path’, some of them extended. By the end of this journey, one realises that the digressions were far more interesting than the conclusion: indeed the journey primarily served the purpose of enticing one into the space in question.

As a ‘guide’ through the near 200 works that occupy Michael Finnissy’s catalogue in the year of his 50th birthday (1996), I shall take the liberty of constructing ‘paths’ of my own; after all, there are an infinite number of such paths, and though none will lead us through the oeuvre in its entirety, I wish to give some impression of the sheer scope and stimulation of Finnissy’s body of work” – (Ian Pace in Tempo )

…and indeed he did. In April 2001 Ian Pace, also an accomplished pianist and musicologist, performed Finnissy’s epic five and half hour composition for solo piano History of Photography in Sound at the Royal Academy of Music to wide acclaim for both the performer and composer alike.

Why aren’t hearing his work on the radio? Why aren’t performances of his work a regular occurrence in his country of origin? Lack of exposure? Too difficult? Too confronting? Perhaps the English as an audience don’t like to be reminded that we aren’t supposed to be comfortable all the time.

Trebuchet got in touch with Michael Finnissy to talk about his work and answer where 2013 finds this fascinating English Composer.

Michael Finnissy : A typical amalgam of writing music, teaching, reading and researching (in this instance: how to write for the harp).

I also moved house in late October, so, a couple of months later, I am still trying to re-locate books and household items.

Would you say you belong to a school of composition: as defined by others or yourself?

Finnissy : No. I have resisted membership of ‘clubs’, possibly to some disadvantage – but I value my freedom and independence, such as it is.

I have not gone out of my way to mythologize myself, but inevitably, to save all the bother and intellectual effort, labels [like ‘New Complexity’] do arise, and what seem like sensible grouping together of composers: Mahler and Bruckner used to be one such pairing, Haydn and Mozart another, The Mighty Handful, Les Six, the Second Viennese School, the Darmstadt serialists. I do not find these groupings useful or meaningful, do you?

Sometimes it seems that genres or schools of composition have been created for record store owners and journalists. However, often enough people compose to form. Have you ever done so? Are composers constrained or liberated by ‘programmatic’ cultural concerns.

Finnissy : When I became aware that I was being compared (usually unfavourably) to Brian Ferneyhough, I made some effort to distance myself, not wishing to compete with a respected friend.

[quote]Quite a lot of the music I write juxtaposes divergent types of pre-existing found-objects with new material that I invent[/quote]

I like to be surprised by people’s work – even if some people find it a subtle difference between Hollywood paper pools and Yorkshire trees, I don’t, and I imagine like David Hockney, I would not like to be found too predictable. But, of course, I too have predilections – perhaps one cannot ever really win with journalists.

I like to be surprised by people’s work – even if some people find it a subtle difference between Hollywood paper pools and Yorkshire trees, I don’t, and I imagine like David Hockney, I would not like to be found too predictable. But, of course, I too have predilections – perhaps one cannot ever really win with journalists.

I am not sure what you mean by ‘programmatic’ cultural concerns. I certainly prefer to be engaged with my cultural and political present, and I find that stimulating – not constraining.

I prefer Verdi to Wagner from a social perspective, but my work is not intended to represent anything except an individual (which is often to say marginalised) view. The ‘visionary’ idea that a healthy society would liberate its artist-members, co-opting them in the creation of Utopia, is rather tarnished by mid-20th century European experience, and in any case I am not convinced that ours is a healthy society. Should I be given the means to change it? Then that might make me something different from, not better than, a composer of music.

English Country-Tunes has formal elements that are quite nostalgic around which wild forms rotate. Would you say that that is a commonality in your work, connecting as you said the ‘human and the abstract’

Finnissy : English Country-Tunes is an allegory. It has components which are ironic and satirical. It is from the same era (1977) as Punk Rock and Derek Jarman’s Jubilee. Each of its eight sections carries the name of an English folk-song, and I needed to deal with ‘nostalgia’, confront it and not simply disparage it.

The structure is intended to gradually reveal and isolate three musical archetypes, and I dramatised my struggle to do that in the music itself – obliterating material, pushing it out of control. What has always drawn me to music is its INHERENT (almost automatic) capacity for connecting the human and the abstract.

You might indeed feel different moments ‘rotate’ or are ‘wild’, but nothing rotates here, and everything is (in some shape or form) more-or-less conventionally and carefully written down.

In the cold light of reason it is just my choice of pitches and durations, timbres and dynamics, onto which, or out of which, we project something less rational.

Some composers perceive harmony as a solution to specific musical problem. Do you see it that way?

Finnissy : Much would depend on what ‘some composers’ might mean by ‘harmony’.

Semantics again.

In a mock Classical Greek sense of the ‘harmonious’ Universe that works like a clockwork toy, maybe you could even say that harmony was the solution to everything. However, it is quite possible to harmonise (by the vulgar definition) a musical idea in many different ways, although to any single individual one way might seem more ‘specific’ than another – more ‘appropriate’ or just ‘tastier’.

I had earlier work rejected by the Society for the Promotion of New Music with the tart little comment: ‘has no sense of harmony’. But you would need to closely study Schoenberg’s ‘Structural Functions of Harmony’ to penetrate that highly encoded comment. This is an example, in actuality, of how we are NOT free – to choose our own harmony.

I am fairly sure that most composers perceive their work, at some level, to be the solution to a specific problem or set of problems. Depending on what you and I might agree to define as ‘harmony’, we might also want to put all our eggs in one basket and propose ‘harmony’ as a panacea. I actually think contrapuntally, and that may not be all that different on the grander scale, but it implies working horizontally across the page, rather than vertically up and down the page.

How do you balance theory and sound? As it can seem that in some of your work you are making compositional statements rather purely aesthetic rather or emotional ones.

Finnissy : I am actually rather an intuitive composer, in some respects a ‘jazzer’. I assemble things, bring stuff together. Of course I cannot switch my brain off, and I am curious about things – so I do lots of exploring and researching.

[quote]Should I be given the means to change it? Then that might make me something different from, not better than, a composer of music.[/quote]

Quite a lot of the music I write juxtaposes divergent types of pre-existing found-objects with new material that I invent, or maybe also extrapolate from the resonances of that ‘engineered’ meeting.

I find stuff that excites me, and I don’t perceive any difference between ‘aesthetic’ and ‘emotional’.

If I stand in front of a canvas by Degas, Rauschenberg or Hockney, I appreciate them for their wondrous intelligence and aesthetic content, indeed how much they teach me about painting and looking, but I also get an emotional charge from them. It is inconceivable to have one without the other.

Many of your compositions use a strong tonal base around which other elements seems to rotate and overlay? Do you think this mirrors the sense of watcher and subject that you have discussed previously.

Finnissy : I do not write tonal music in a tonal way – I write it ‘atonally’. The aims are different. I compose WITH tonality, I enjoy getting my hands dirty with it. I do not try to simply repeat what is already there in the past. It is always me doing it, and IT is certainly not intended to stand for anything ‘outside’ of me.

We do, however, acquire some sort of critical relationship to tonal music of the past. It is constantly thrust under our noses: Old tonality is not inevitably going to be interesting or beautiful.

Often when I hear you speak about the structural systems of composition, faking, idiomatic construction, parody, I’m reminded of the sociological and theoretical work on discourse by Michel Foucault and Pierre Bourdieu. Have these thinkers been an influence in any way?

Finnissy : There is certainly a considerable influence on my work from the writings of Foucault, Barthes, Baudrillard and Deleuze, writers who are actively and passionately concerned to dissect and analyse the world. I am highly concerned about the quality of my own compositional ‘discourse’.

Do you compose for yourself or an audience, and at what stage of a piece’s life do you marry the two?

Finnissy : Stravinsky already answered this perennial question so well – so, to paraphrase and slightly expand: I write for the hypothetical, and hyper-critical, ‘other’ that is also myself. I don’t think you should be tempted to generalise who or what an ‘audience’ is.

Finnissy : Stravinsky already answered this perennial question so well – so, to paraphrase and slightly expand: I write for the hypothetical, and hyper-critical, ‘other’ that is also myself. I don’t think you should be tempted to generalise who or what an ‘audience’ is.

One rarely gets to know every member of an audience, and if you did, would you really want to spend ‘quality time’ with, be friends with, live with, make love to, or resemble them in every particular?

How then could I be writing to satisfy or entertain or titillate two thousand, two hundred, twenty or even two people? These expectations would only arise if one was interested in domination, in power and control.

What is the pinnacle of achievement for a composer? Is there a universal answer or is it subjective?

Finnissy : It is subjective.

Which scale do you think is overused?

Finnissy : Any musical idea can seem stale or overused in the wrong hands, and in the right hands even the most mundane thing can work magic: this seems to be the lesson in Beethoven’s work, that very basic and fundamental, even commonplace, musical ideas can be worked on and explored to yield the most fantastic and unexpected results.

It’s been written that your personal themes have come to the fore in pieces Shameful Vice and Seventeen Immortal Homosexual Poets. To what extent do you see this as the case and is it the case that these comments are equating ‘sexual’ with ‘personal’?

Finnissy : My ‘personal themes’?! Does homosexuality seem ‘exceptional’ and deserving of special consideration then? Would a heterosexual composer only be considered to have ‘personal themes’ that were underwritten by their sexuality?

I am concerned about ignorance and stupidity, about pointlessly brutal discrimination, and about the casual abuse of power and capital. I have travelled very extensively and witnessed these issues everywhere in the world: maybe a reason for not writing anodyne or prettily cheerful music.

That said, you seem like to describing pleasing sounds as ‘sexy’ in a interviews that suggests something satisfactorily comprehended by the heart and the mind, is that Jouissance an end in itself?

Finnissy : I make the mistake of trying to explain, and defend, my work and the thinking behind it. Undoubtedly it would be preferable not to be asked. The entertainment media could not survive without ubiquitously mentioning of sex.

As language grows shabby with over-use (like musical scales?), I have to find increasingly sharp and noticeable expressions simply to be listened to at all. ‘Sexy’ is a few notches up from ‘nice’ or ‘pleasant’ – remember I am trying to combine human and abstract! I write music NOT literature.

What are the important things to consider when listening to any composition?

Finnissy : Timing. Spatial awareness.

I’ve always seen your work as more reportage than personal statement. To what extend do you agree?

Finnissy : As time goes by, I increasingly wonder about the work my father was doing when I was a child – documenting the war damage and rebuilding of London after the second World War – and how much this might have influenced my ‘creative drive’ or my ‘aesthetic outlook’ or my sense of my place in society: as you say, reporting and documenting my experiences and the experiences of others, not as a photographic archive but as a musical one.

When I was a student, there was much brave talk of doing away with the ‘museum culture’ – and I resolved to create my own collection of personally significant musical ‘objects’ responding to, and representing every genre, every period of history, every tradition and nationality. It’s only a part of the quest, but probably significant.

It’s difficult to talk in generalities about your work. Each piece seems specific. If someone wanted to know about Michael Finnissy the person would your music necessarily be the best way understanding you? Or do you approach composition from an ‘objective’ distance?

Finnissy : My friends and family can tell you about ‘the person’. They probably know better than I do what the relationship is between the music that I dream up and write, and the self. Although most people only see what they want to see. I do not pretend a God-like ‘objectivity’ in my work: I am very much present in it, with all my failings.

Is your music a greater or lesser part of who you are? For instance some musicians are consumed by their art and others see it as a tool for their own expression, of which music is a part.

Finnissy : I don’t have a life other than that as a composer, that’s why I am here.

You’ve been lauded and recognised widely, is there anywhere you’d like to take your music that you haven’t explored as yet?

Finnissy : Have I? I have also been reviled and dumped on too – let’s keep a sense of perspective here. I am constantly exploring, making fresh mistakes, finding gorgeous things to do. I have no intention of stopping.

Where can people find out about performances of your music and releases?

Finnissy : I have a website [www.michaelfinnissy.info] and several publishers [principally Oxford University Press, Ricordi Deutschland, Universal, United Music Publishers] and incredibly supportive CD companies [NMC, Metier/Divine Art]. But for live performances you will have to be prepared to travel a lot further than the South Bank!

Are you currently working on any new pieces of music?

Finnissy : Yes, for a performance in Taiwan in October.

Are there any themes that you haven’t approached that you’d like to?

Finnissy : Probably.

When is a piece finished?

Finnissy : It varies from piece to piece, so there isn’t an easy generalisation. I suppose that the performance ‘completes’ the work in some ways, but I do, occasionally, get ‘needy’ things off the shelf and re-work them, if I am not satisfied with how they have gone.

After all, I wouldn’t want to leave anything in less than the best state I could manage.

//For more information please visit Michael Finnissy’s website.

References:

The Panorama of Michael Finnissy (I) Ian Pace, Tempo. New Series, No. 196 (Apr., 1996), pp. 25-35. Published by: Cambridge University Press. Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/944457

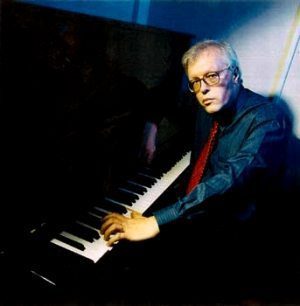

All Photographs Courtesy of Michael Finnissy

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle

Nice interview with this fascinating composer.

However, the performance of English Country Tunes on Youtube which you provide a link to is well filmed,but a travesty.

Try and follow it with a score…the charlatan ‘pianist’ is just thrashing around.

I ought to clarify that pitch accuracy isn’t top priority in playing a piece like this (same applies to the Eonta by Xenakis) but to be so far off the mark and not even bother to read a basic performance instruction for the last section of the piece is just plain stupid.

Thanks Giles,

We agree, following a score is very important in classical music – some might say essential.

Would be keen to know who you thought has recorded the definitive version of English Country Tunes.

…I’m guessing Finnissy himself. 😉

Not sure about the idea of a definitive recording of anything, but the composer himself does attempt to what it written ,whereas Nika Shirocorad doesn’t bother.

Compare 08:36 of NS with the 10th instalment of English Country Tunes from the composer. As you can hear, there is no relationship between them, even though they are the same piece.

The former sounds like an adolescent tantrum whereas the latter has an almost macabre quality with the hands at the extreme ends of the keyboard (ie. what is written)

ミニウェディングドレス